Parkour or, as its practitioners also refer to it, l’art du deplacement [the art of movement], stands out among other recent expressions of urban culture. The discipline consists in moving through the urban environment, overcoming obstacles along the way (fences, walls, etc.), in the most fluid and efficient form possible, aided only by one’s body.

The starting point for this project was the video recording of a parkour encounter in the Madrid Civil Cemetery. The session began by tracing a course, from point A to point B, in the cemetery and inviting a group of traceurs (practitioners of parkour) to cover the distance between the two points. Parkour is a non- competitive discipline and traceurs opt instead for “meetups” in which they share and compare their progress, techniques, and other elements of the discipline. Generally speaking, once a course is established, each traceur will cover it in his or her own manner, while respecting the rule of never backtracking.

The Madrid Civil Cemetery, together with the Almudena Cemetery and the Jewish Cemetery,

is part of the Necrópolis del Este [Eastern Necropolis]. Spain’s civil cemeteries originated in the Royal Decree of April 2, 1883, stating that municipal councils governing a judicial district or towns with more than 600 inhabitants were required to provide a separate enclosed space next to the Catholic cemetery for the burial of non- Catholics, and with its own separate entrance.

The Madrid Civil Cemetery opened on September 9, 1884, and the list of those buried there includes presidents of the First Republic, Estanislao Figueras, Francisco Pi y Margall, and Nicolás Salmerón; the founder of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party, Pablo Iglesias; socialist leaders Julián Besteiro and Francisco Largo Caballero; writer Pío Baroja; philosophers Pedro Laín Entralgo and Xavier Zubiri; communist leader Dolores Ibarruri; Republican officer and general in the Armies of the USSR, Poland, and Yugoslavia Enrique Lister; pedagogue Francisco Giner de los Ríos; urban planner Arturo Soria; and artist Wolf Vostell.

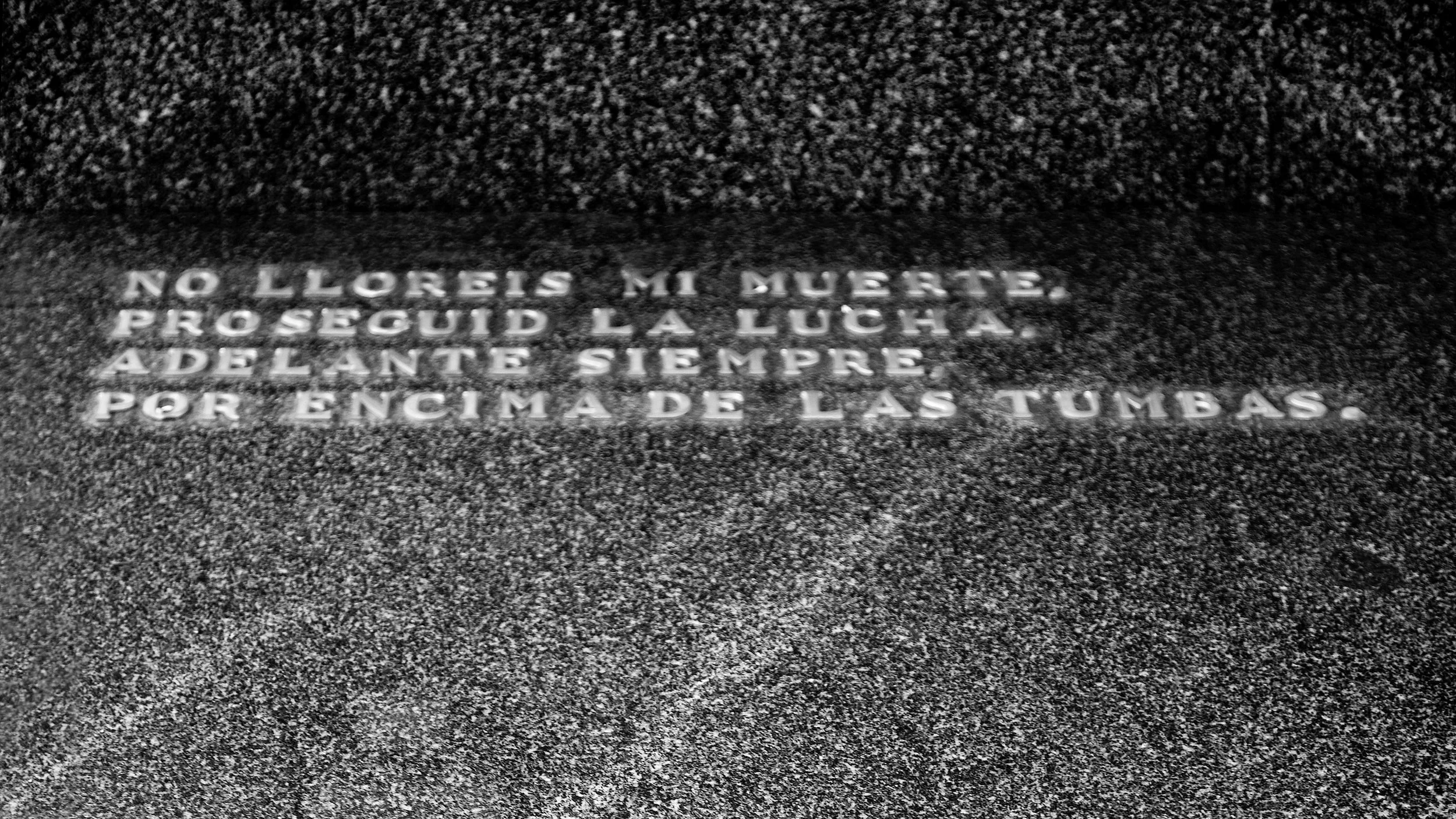

The character of these civil cemeteries is evident in the epitaphs on the tombstones, such as “Love, Liberty, Socialism” or “Freedom and Reason Will Make You Strong”.

Certain interpretations of parkour recognize an evident connection with situationist psychogeography, a discipline in which, rather than be imprisoned by daily routine, the citizen confronts urban situations in a radical new way. Just as the situationist psycho-geographer perambulates the city, establishing a personal cartography and creating his or her own emotional territory inside the urban planner’s organized city, the traceur charts a unique course across urban obstacles and imposes this route over the functionality of the city. One of the mottoes of parkour is, “The day that everything is flat, we’ll be dead”.

When traceurs jump over a wall or a handrail or climb a building, they are wholly indifferent to its function or ideological content and, therefore, are unconcerned with the presence of architecture as building, or the composition of the logically disposed space or materials comprising a coherent urban entity. By focusing solely on specific architectural elements (walls, corbels, benches, railings, stairs), the traceurs reject the existence of architecture as an indivisible three-dimensional entity recognizable only as a whole, treating it instead as a floating system of separate, isolated physical elements, where the architect’s considerations with respect to users, and their subordination of the body to space and design, are obviated. The traceur’s performative body has the capacity to take on a given system and its predetermined circumstances and extract what is useful to him or her, dismissing the rest.

Parkour reproduces architecture in its own way and, like the situationists’ “drifting”, it draws new maps of the city. In an aerial map, an entire city can be represented simultaneously, in a single glance, but if there were such a thing as a traceur’s cartographic model, it would be unlike any conventional or totalizing map.

New cartographies would arise, comprisedof disparate objects in a sequence (linear cartography), with some objects “represented” once (isolated cartography), others several times (repeated cartography), and others indicating points to which one returns repeatedly on different occasions (cyclical cartography).

However, and despite the relationship between the concepts of situationist psycho-geography and parkour, we must not forget its French origins. Frenchman David Belle, the son of a military man, learned Georges Hébert›s méthode naturelle from his father. The method, a form of military training in which obstacles encountered in natural settings are tackled using the body, was later applied to the city with its fences, walls, roofs, etc. Under normal circumstances, an obstacle prevents us from going further, it paralyses us. But in parkour, everything is perceived as an obstacle that may be used to create movement.

Ser y Durar. Video stills. Single channel video, 18' 40". [La Almudena Civil Cemetery, Madrid] DEMOCRACIA, 2011. Still photo: Ximo Michavila.

Colección de sudaderas Ser y Durar. 5 Sudaderas bordadas DEMOCRACIA, 2011 Ser y Durar Sweatshirt Collection. 5 Embroidered Hoodies DEMOCRACIA, 2011

Ser y Durar. Video stills. Single channel video, 18' 40". [La Almudena Civil Cemetery, Madrid] DEMOCRACIA, 2011. Still photo: Ximo Michavila.

Parkour’s principle motto is “to be and to last”. Although this is generally interpreted to mean that the traceur should not put himself in danger and improve daily, and should avoid competing with or trying to outdo others, it also seems to refer, on the one hand, to the traceur’s association with a specific community and, on the other, to fulfilling his or her commitment to that community. Another motto, deriving from the first, makes a clearer reference to the military origins of this urban sport: “Be strong to be useful”. Interestingly, the members ofthe parkour community all share a wish to “be useful”, not directed at any concrete cause, but pointing to a certain humanist philosophy. And this humanism, paradoxical as it may seem, has military roots, which shouldn’t surprise us, given that modern day armies seem to focus mainly on “humanitarian” and “peace” missions.

From this perspective, parkour groups can be understood as a kind of urban guerrilla, which in the context of our feel-good, consumer societies uses a military technique as a tool for engaging in a critical practice of the city. Skateboarding can also be understood in this same sense in that its main critical objective is to propel the body through urban space, in direct interaction with the city’s modern architecture and in a rejection of other values and ways of inhabiting the contemporary capitalist city.

Another important aspect of the practice of parkour is its temporal nature. Memory is erased during one’s practice; the traceur does not set out from any given historic memory, but instead from a quotidian memory based on his or her personal routes. Thus, the traceurs negate the “historic” vision of the city; they are totally alien to the processes of its construction and its landmarks, so that the urban stage appears before them as a structure without a past, a system of elements that can be recombined in every new session.

Ser y Durar. Video stills. Single channel video, 18' 40". [La Almudena Civil Cemetery, Madrid] DEMOCRACIA, 2011. Still photo: Ximo Michavila.

Ser y Durar. Video stills. Single channel video, 18' 40". [La Almudena Civil Cemetery, Madrid] DEMOCRACIA, 2011. Still photo: Ximo Michavila.

When we suggested a meetup at the Madrid Civil Cemetery to a group of traceurs our aim was to activate a sort of monument-in-negative, owing to the ephemeral nature of the meetup, which would incorporate both critical practices tied to urban culture and a salute to those members of armies, social organizations, and political parties who, moved by humanitarian values, aspired to a utopia at a time when the great emancipatory stories of Modernity still made sense. And although the meetup took place in a location steeped in memory and profound symbolic meaning, given the nature of parkour, the traceurs were unconcerned with the historic sediment of the place and focused purely on its spacial and constructive qualities.

Considering that a substantial part of society’s egalitarian and revolutionary aspirations are buried in the Madrid Civil Cemetery, the proposed psycho-geographic route through the space hoped to establish a tension between the mobility of the parkour practice and the immobility of the necropolis, between the dreams of progress reflected in the tombstones and a practice based on popular culture that has nothing to do with a period in which the revolution never actually took place. The epitaphs created a narrative defined by the traceurs’ movements: on the one hand, as mentioned earlier, the traceurs’ motto –“To Be and To Last”; on the other, one of the epitaphs at the Civil Cemetery that reads, “There is Nothing After Death”.

1- Nada hay despues de la muerte. [There is nothing after death] Digital Print, 89 x 118 cm. DEMOCRACIA, 2010. Photo credit: Ximo Michavila./

2- No lloréis mi muerte. Proseguid la lucha. Adelante siempre. Por encima de las tumbas. [Do not mourn my death. Keep on struggling. Always ahead. Stepping over the tombs] Digital Print, 118 x 89 cm. DEMOCRACIA, 2010. Photo credit: Ximo Michavila.

3- Son las cosas que no conocéis las que cambiarán vuestra vida. [The things you do not know will change your life] Digital print, 89 x 118 cm. DEMOCRACIA, 2010. Photo credit: Ximo Michavila.