I

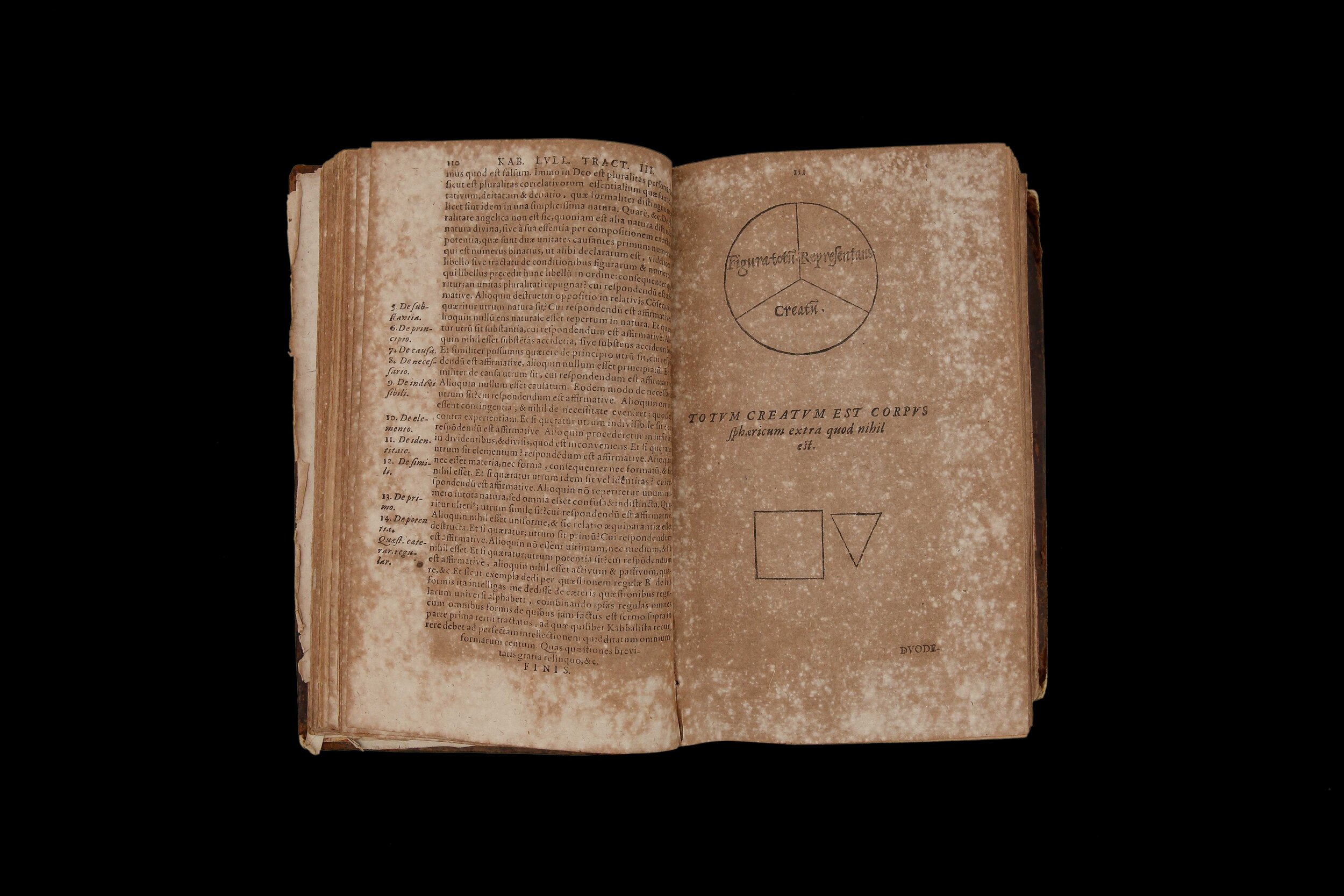

The aim of wisdom, in opposition to division, is union. This axiom is similar to the principle contained in the famous Emerald Tablet text, which says “that which is above is like that which is below”; in other words, what moves in the sky moves on Earth and vice versa.

II

God created the reality of things ex nihilo, a reality theologically understood as the World. His first actions were the creation of Heaven and Earth and the separation of the Waters and the Earth. Only after this does He understand that there is Darkness and says:

וַיֹּ֥אמֶר אֱלֹהִ֖ים יְהִי–א֑וֹר וַֽיְהִי–אֽוֹר

Light, unlike Darkness, did not exist in the beginning: God, defined in this essay as universal consciousness, had no contrast and no sense of vision. Wisdom was an inner concept with no reflection in nature.

III

From this point forward, God created things with a sense of vision. A world that is better understood through sight. Sight that is activated only by means of light, the equivalent of universal consciousness: understanding. An analysis of the preceding leads to the conclusion that there can be no understanding without light, and that darkness can only be understood in comparison to light.

IV

The Greeks believed that every time a hero died he became a star. And that heroes watched and protected their descendants from Heaven above. This mythical image allows us to approach the stars and recognize our blindness with respect to the way the universe was understood, sometimes defined as a void filled with darkness.

IIIa

Giordano Bruno was burned in Rome for defending the existence of a multitude of universes.

IIIb

Death by burning in the name of the Inquisition was intended to cleanse the soul and body of sin and bring consciousness directly to its source of origin, which is God: the light and fire of the Universe.

IV

Bruno’s Art of Memory proposed an active philosophy, which could be used as an organizational tool for learning and thought. A way of seeing thought as a “living tool” that can bring us closer to the light of understanding. Bruno organizes Understanding according to hierarchies or different levels, based on its proximity to the light, or as appearing gradually, based on its distance from darkness. This panorama introduces ideas such as the shadow of light, in which light is the cause of things and darkness is ignorance and death.

IVa

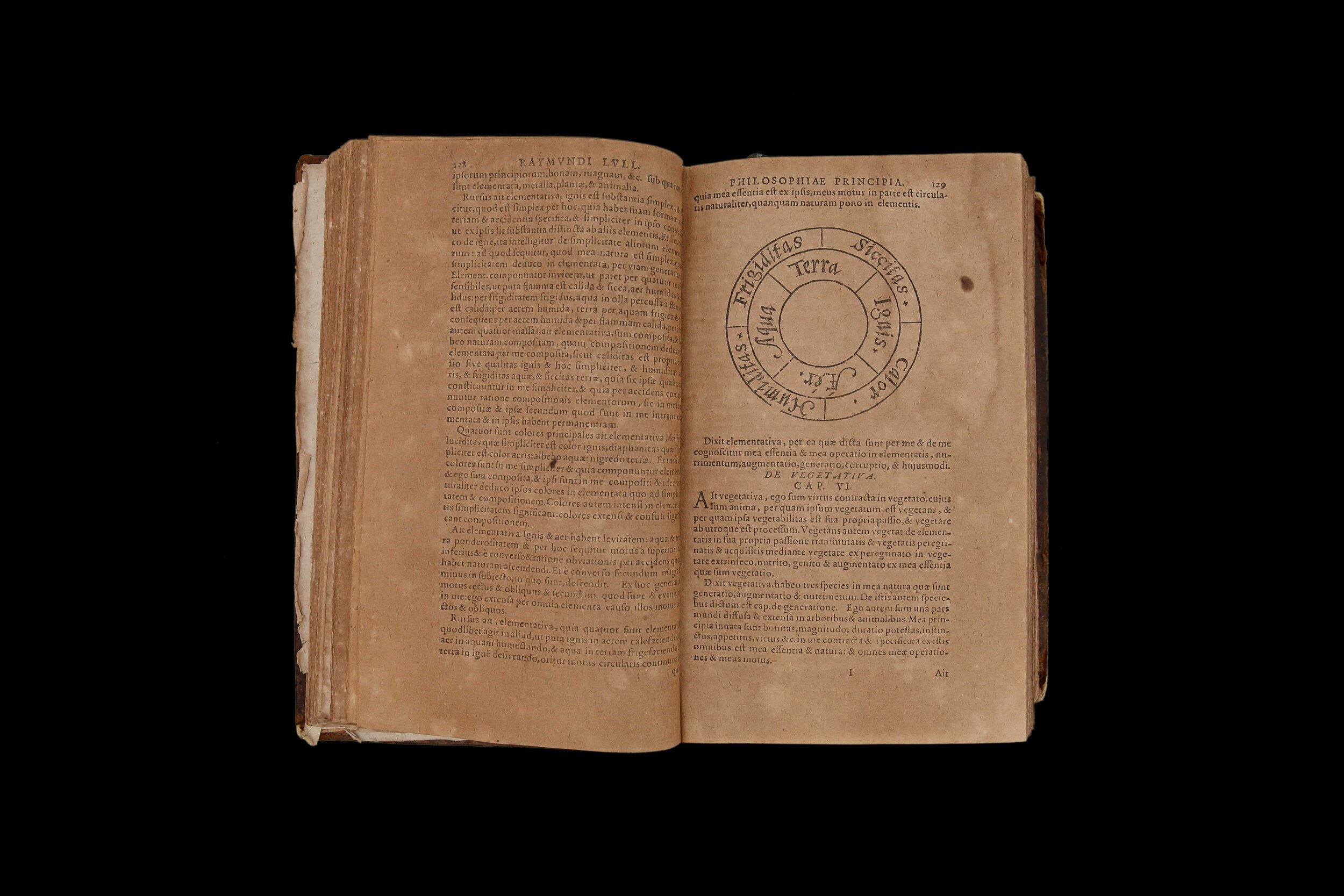

During the century in which Bruno lived, implementation of the “scientific method” and the development of new instruments of exploration and measurement, such as the telescope, prolonged our perception of nature as an extension of our physical capacities. This led to important discoveries, while aiding in the reconsideration of the dusty paradigm inherited from the already decrepit and dark world of scholasticism. Copernicus’s newly proposed system, which opposes Tolomeic cosmography, can be easily observed by means of the telescope: The Sun is at the center of the solar system and the stars behind it are other solar systems. Perhaps, without knowing it, Bruno’s system luminously and directly refers to a vision of the universe in keeping with these recent discoveries.

V

As with the prisoners in the Platonic cave, the world of ideas is a projection of shadows. In Bruno’s book, On the Shadows of Ideas (De umbris idearum, 1582), he points out that shadows are the forms that Reason takes during the learning process, and that organize it. These shadows can be used as images and symbols to then organize the knowledge of things.

VI

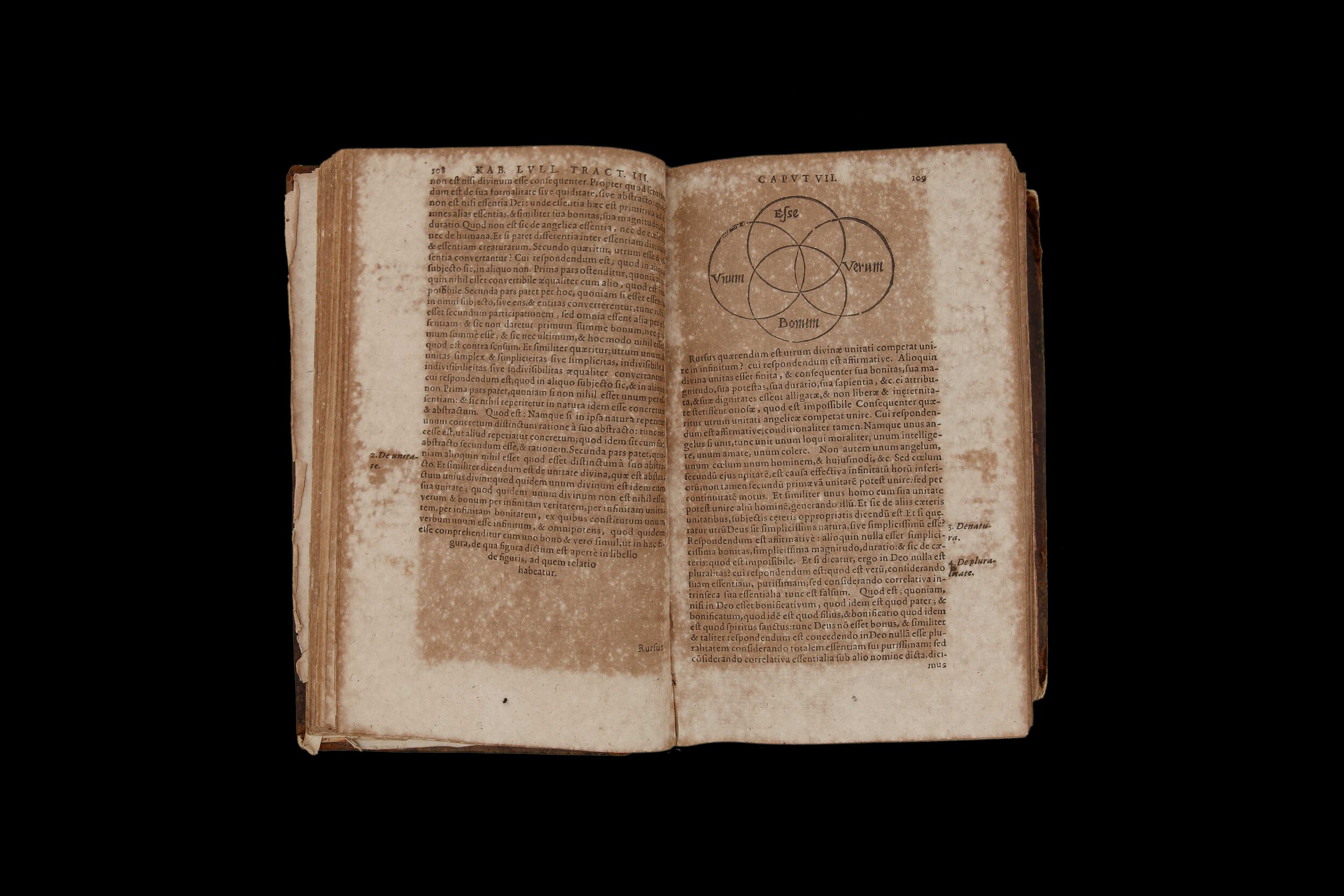

Bruno suggests that there is no shadow without reflection. Ideas are described as shadows of divinity, perhaps a distant repercussion of or analogy with the Creation story in the book of Genesis; that is, first came the shadow, and consequently, an understanding of the light.

VII

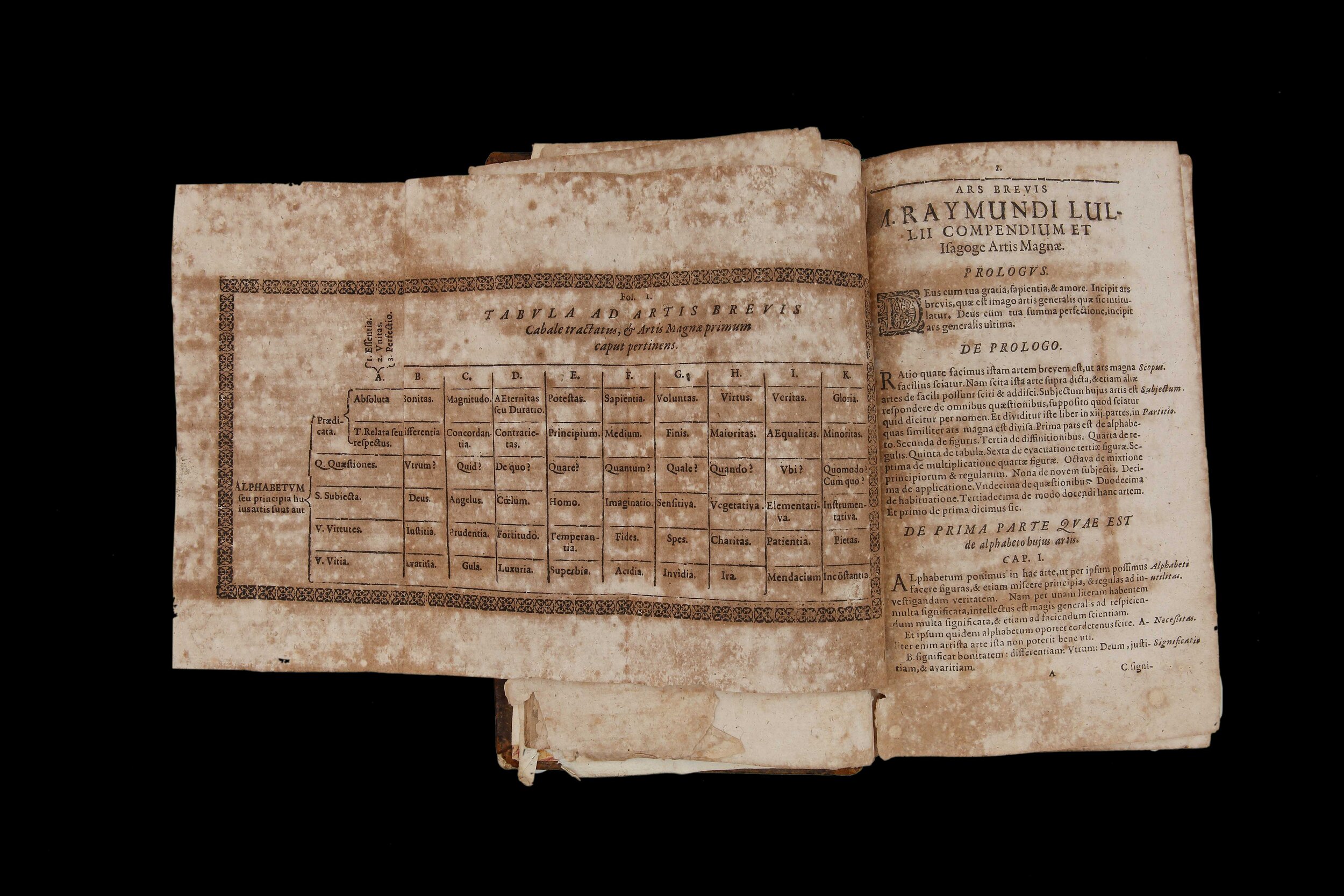

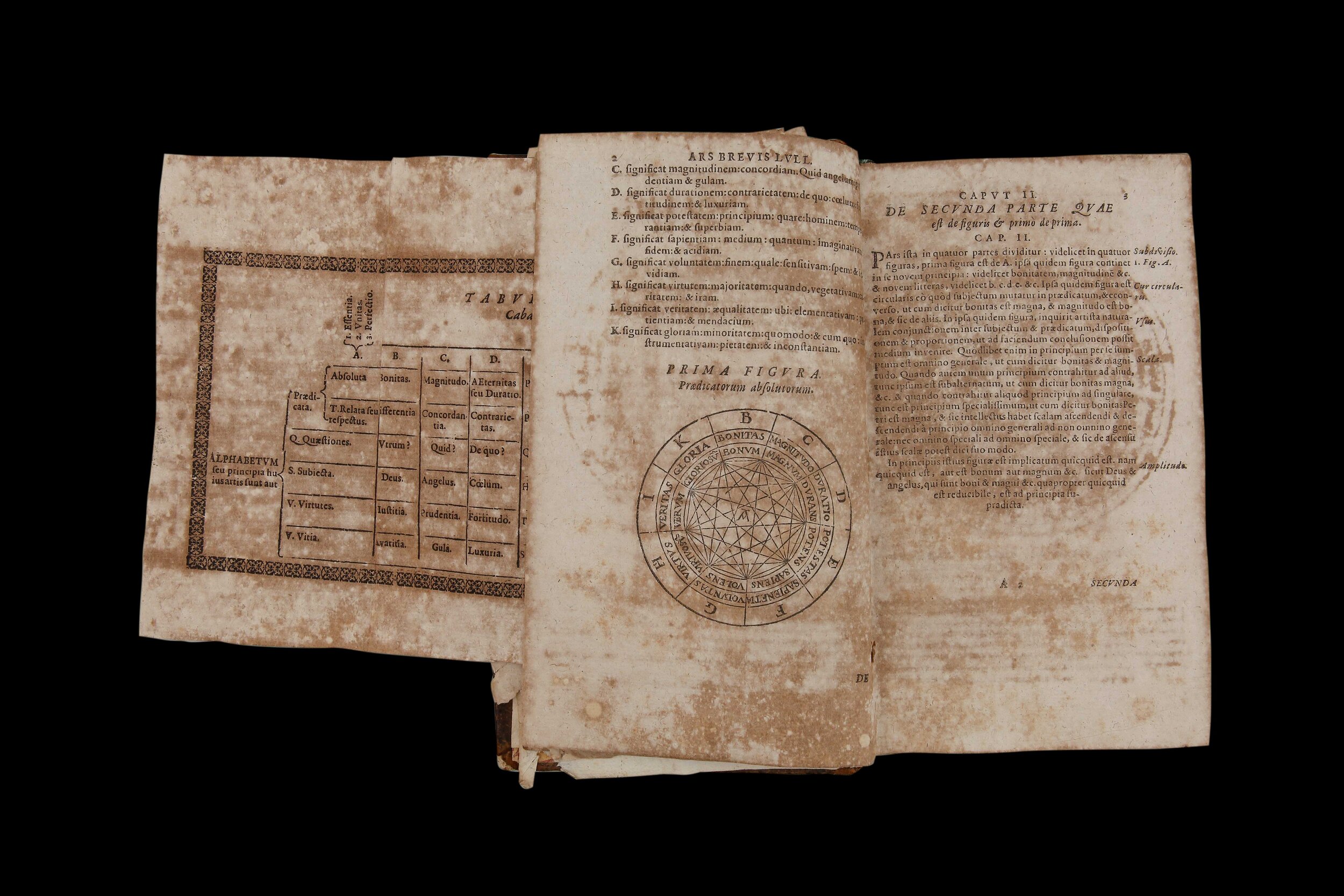

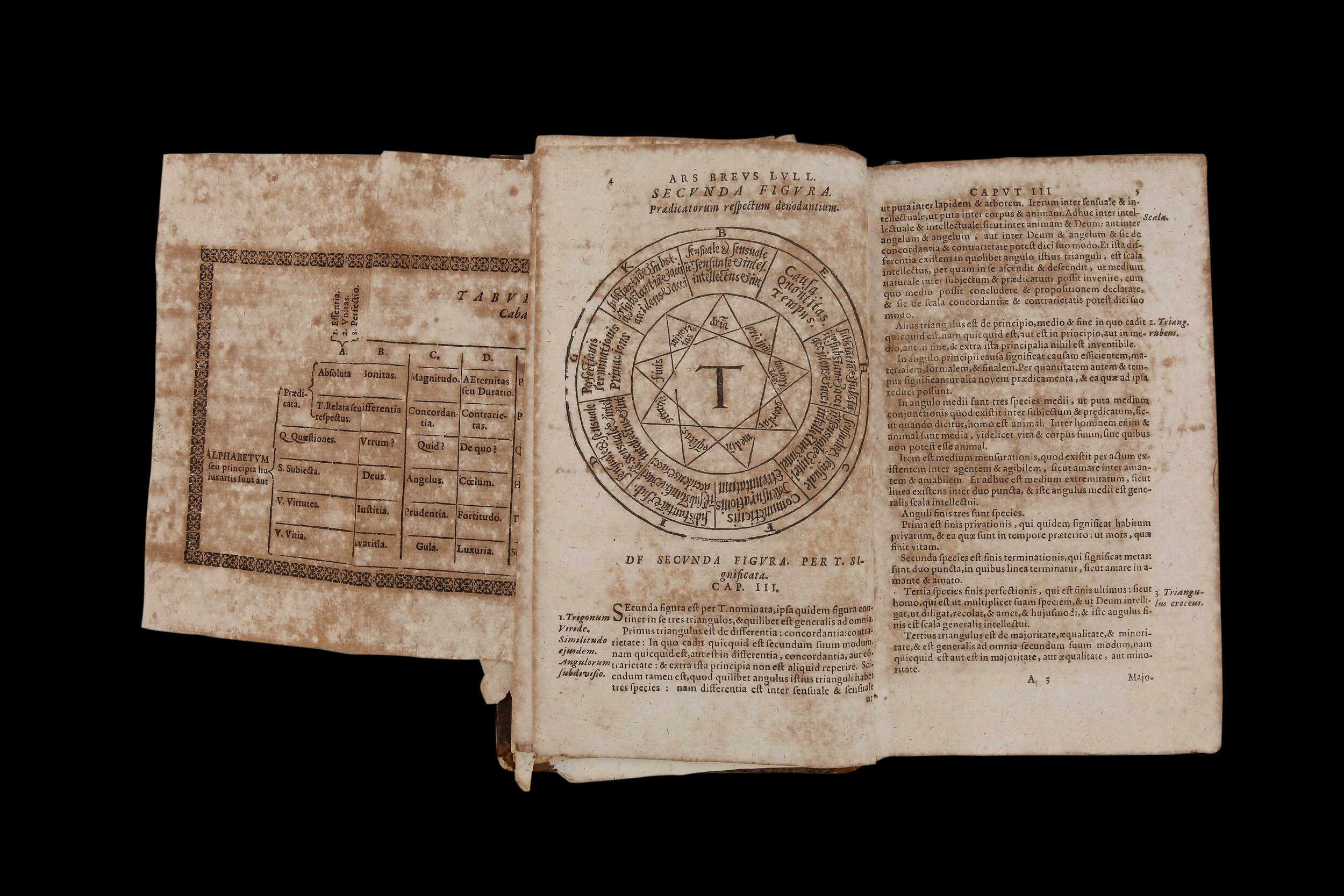

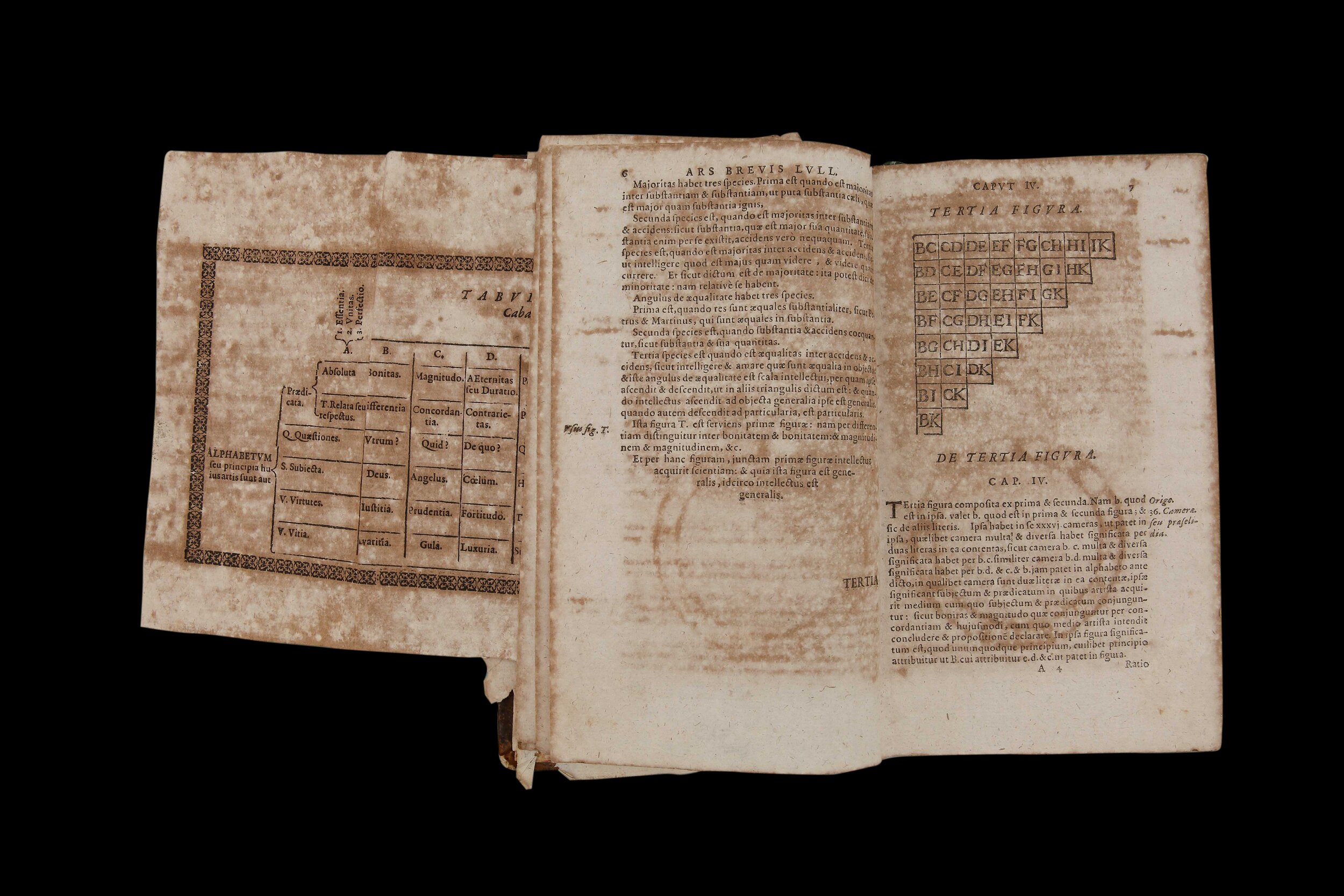

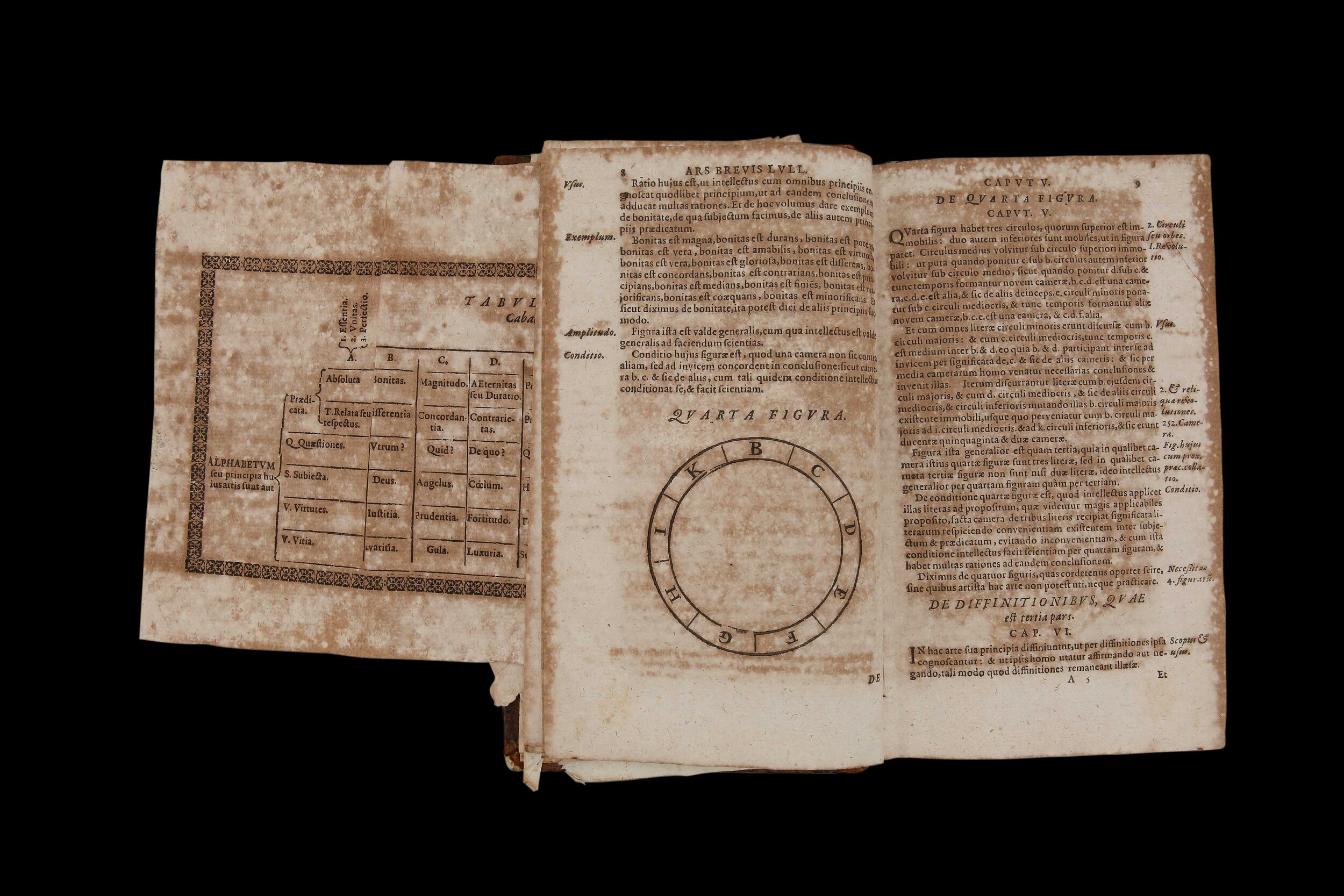

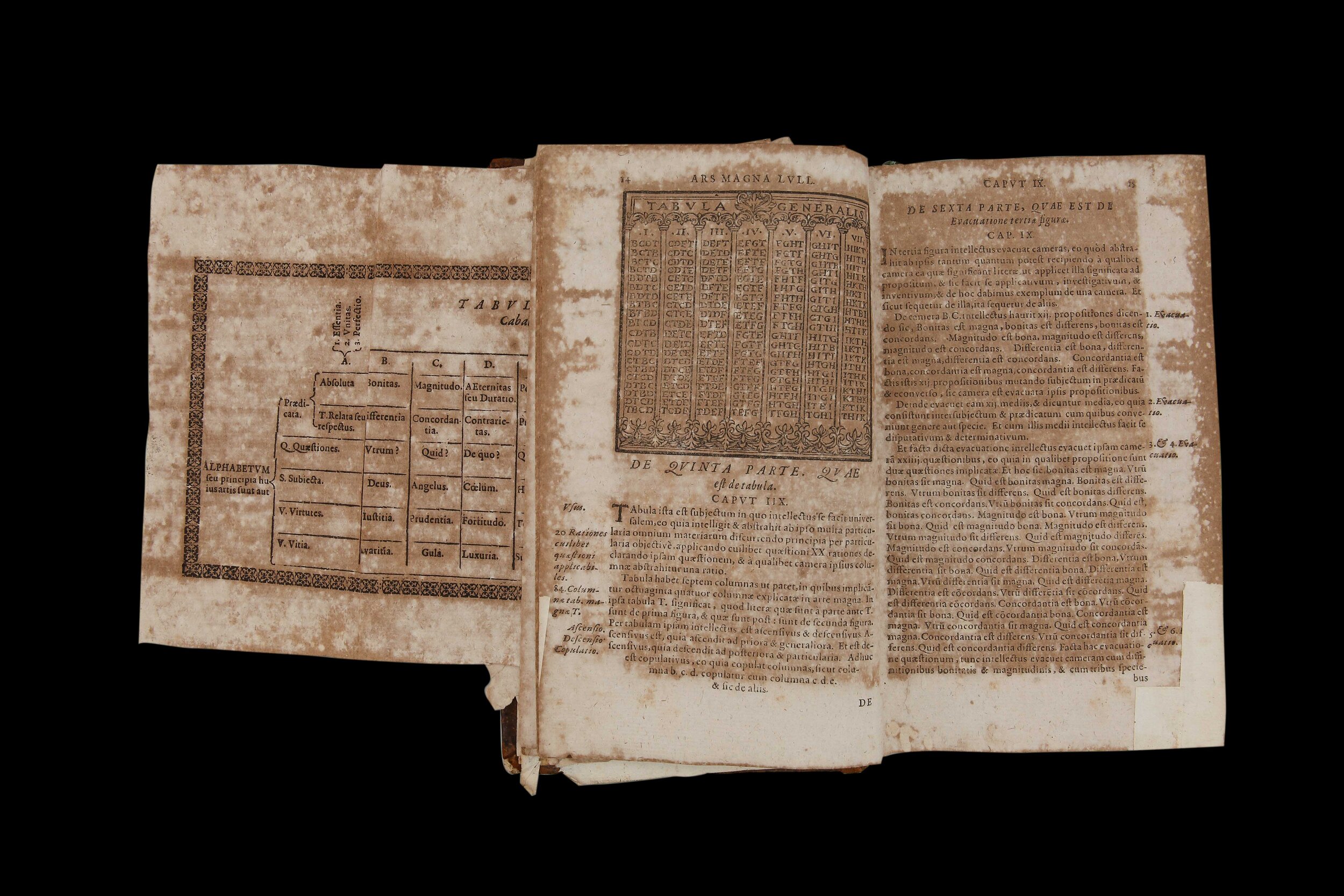

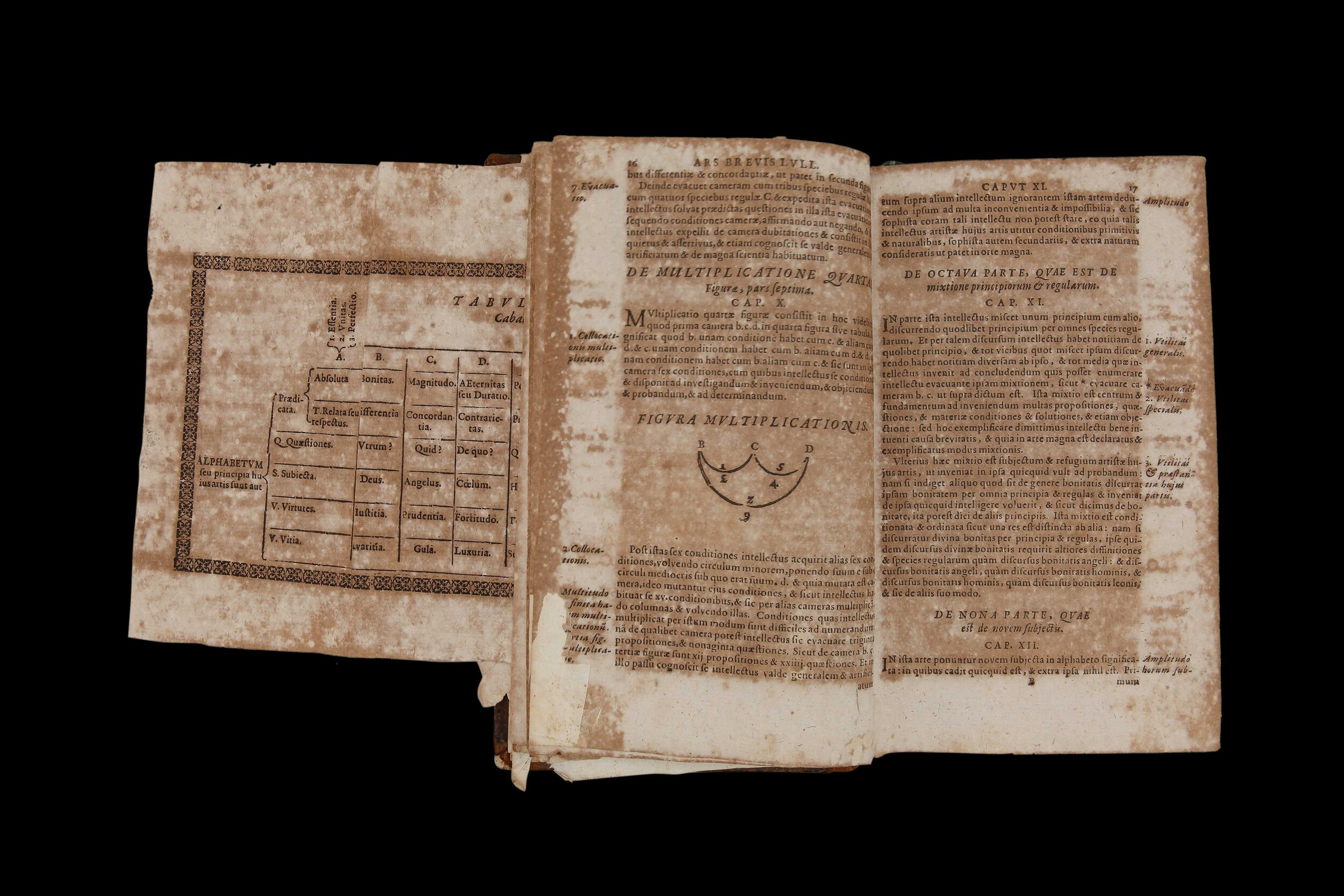

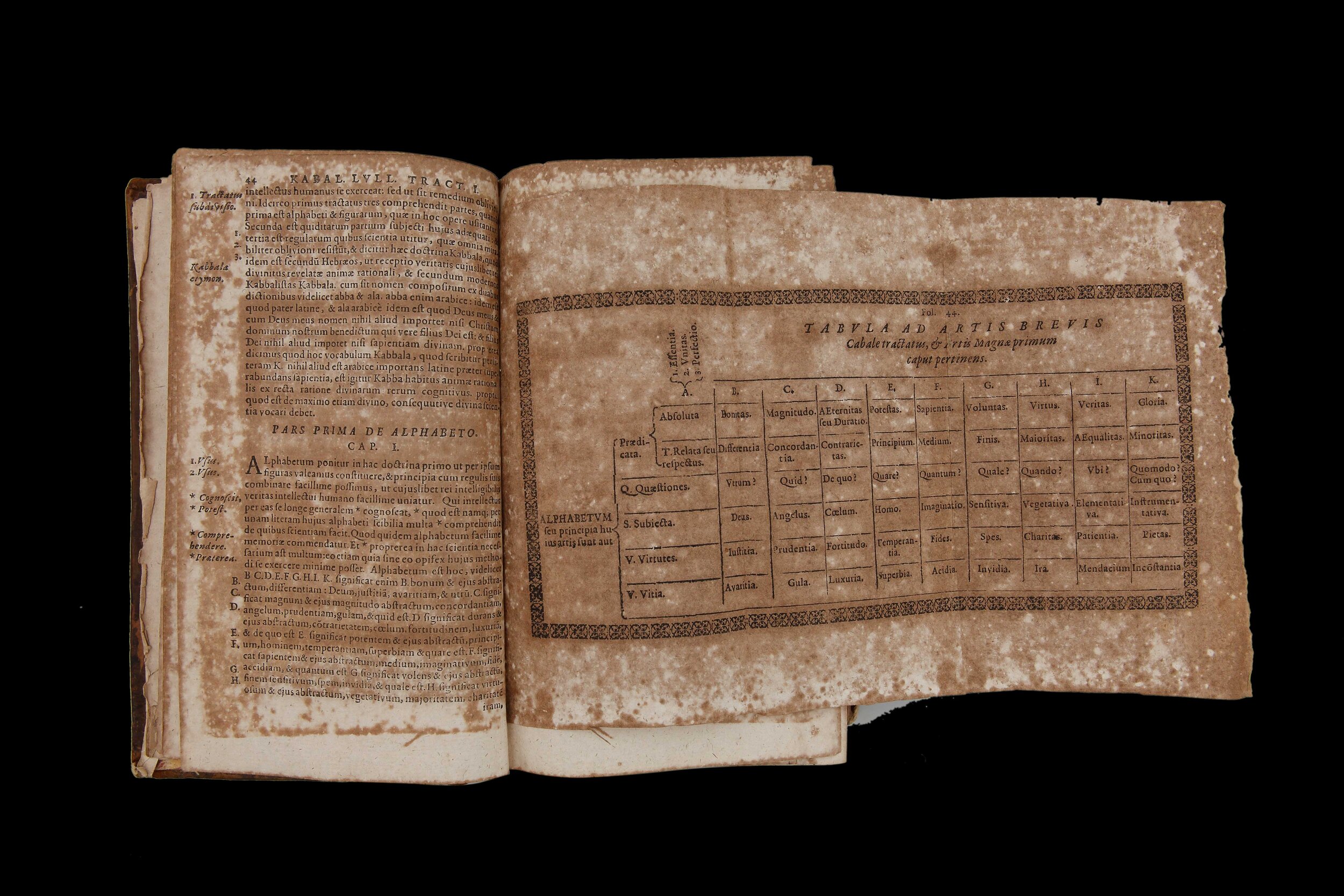

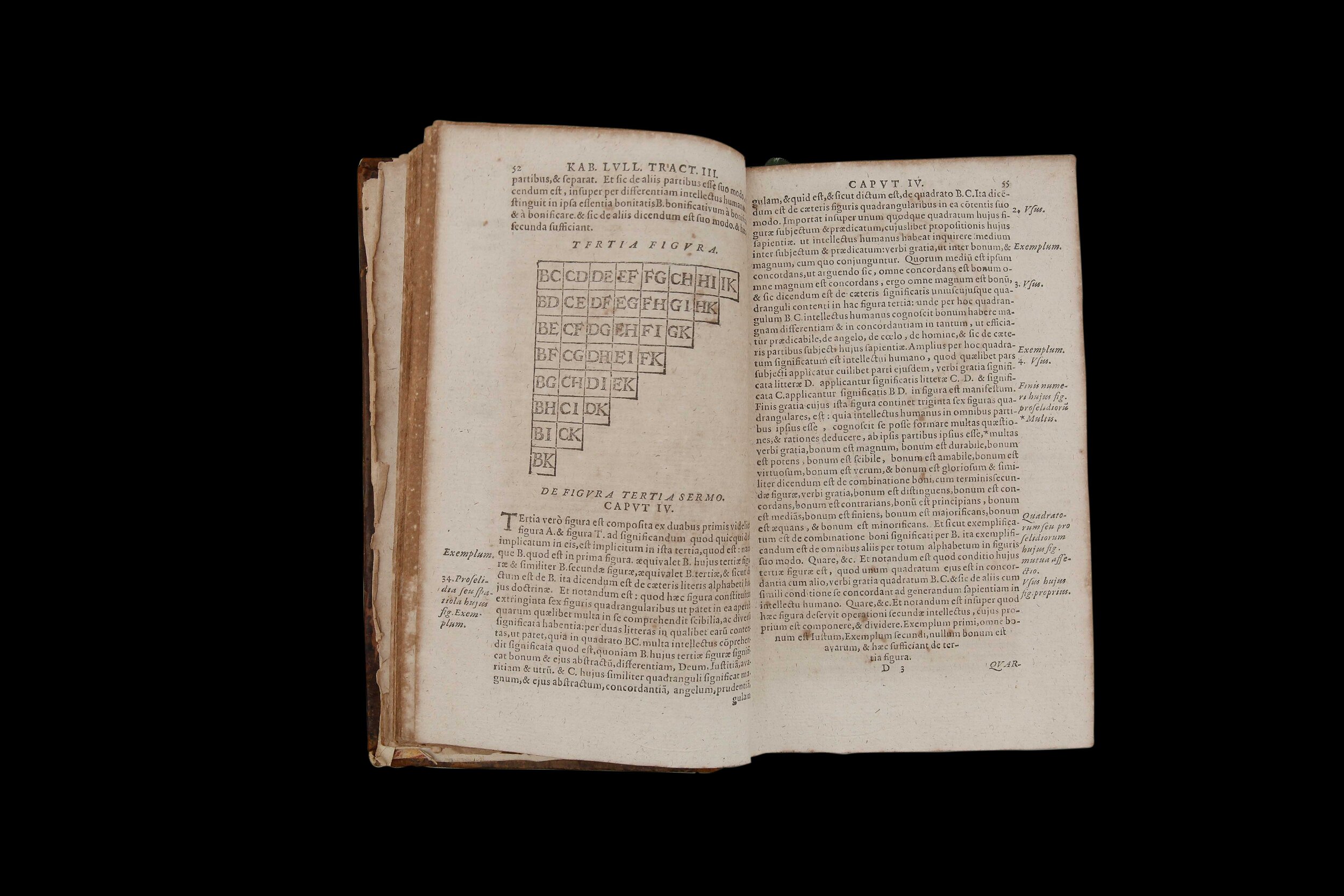

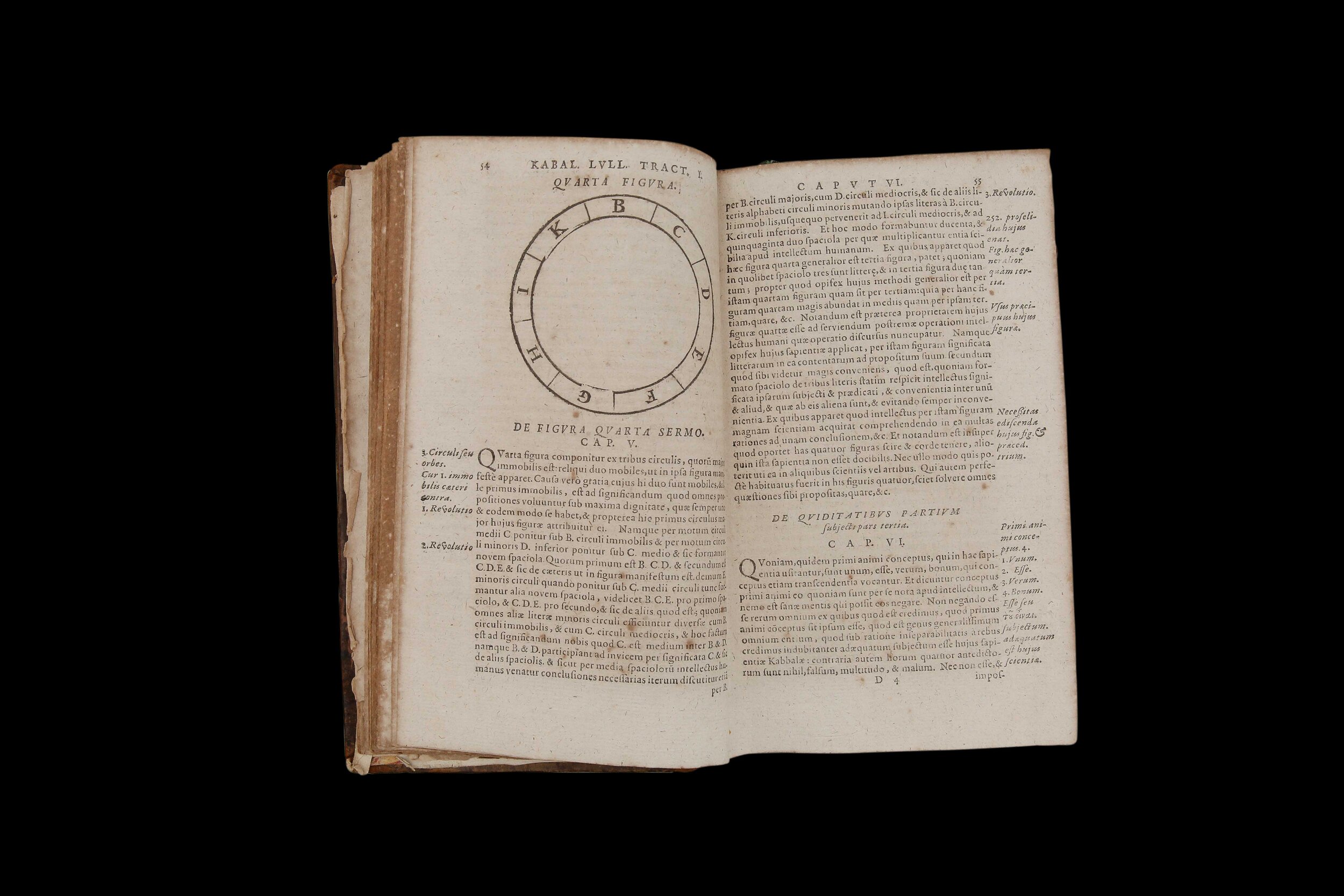

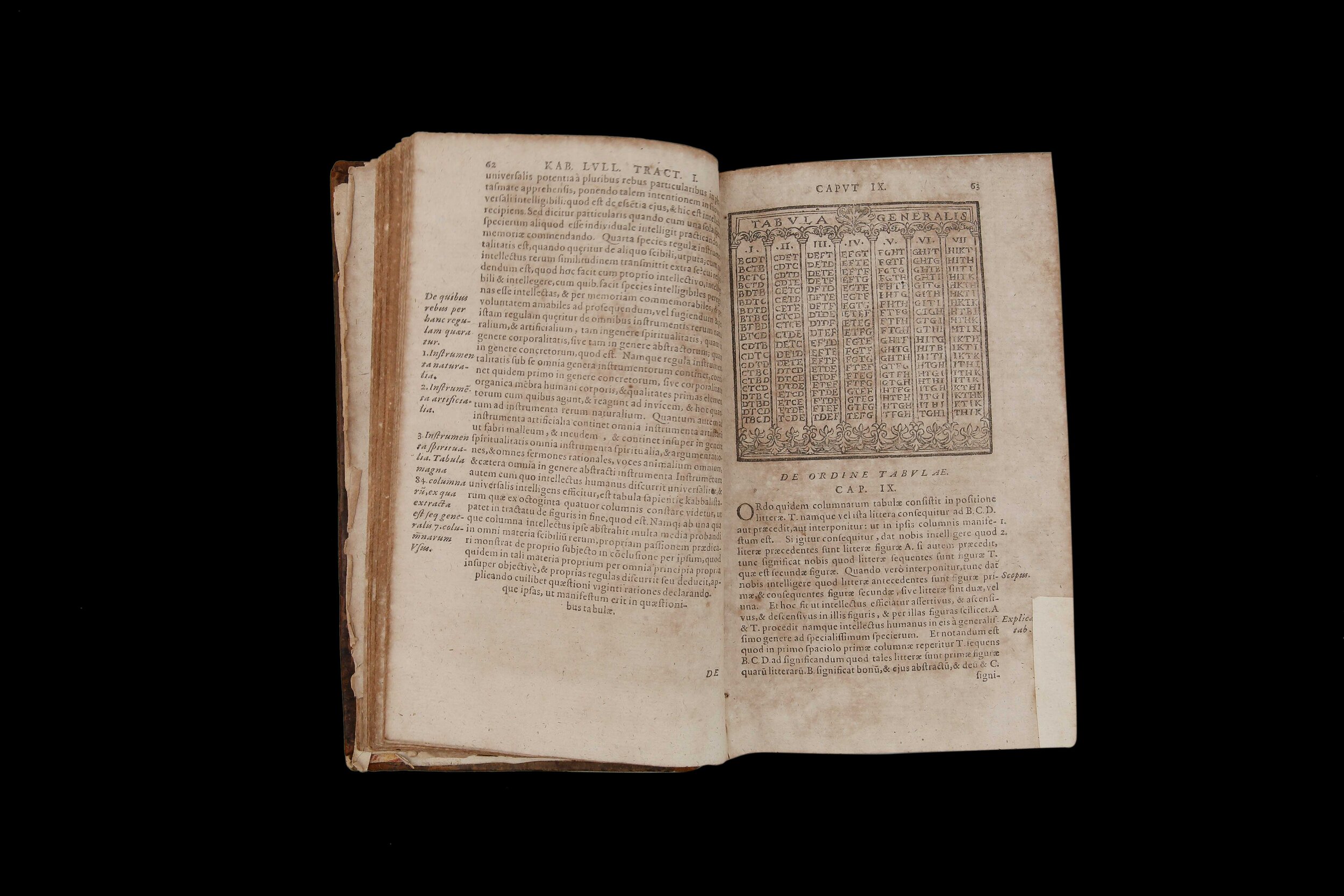

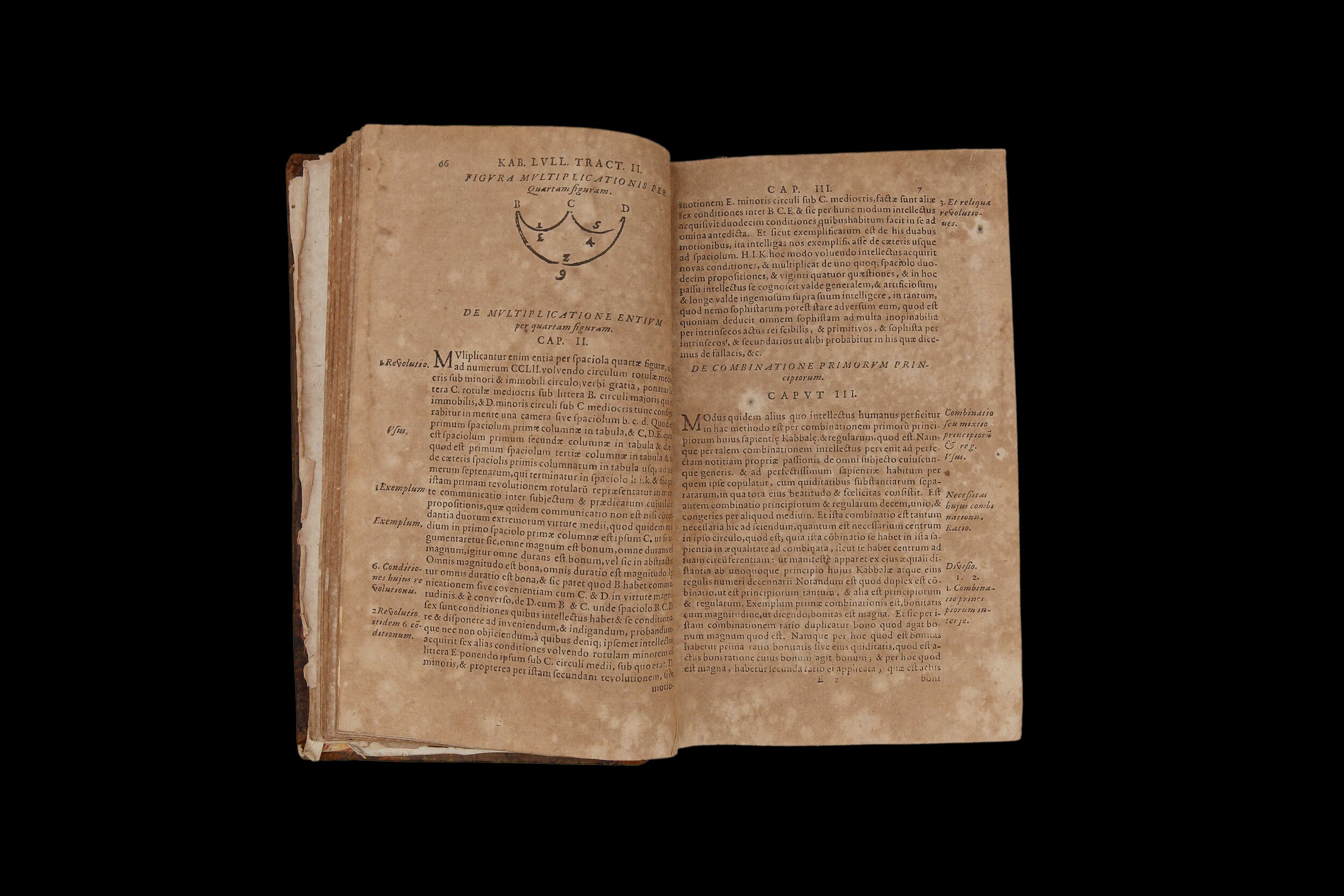

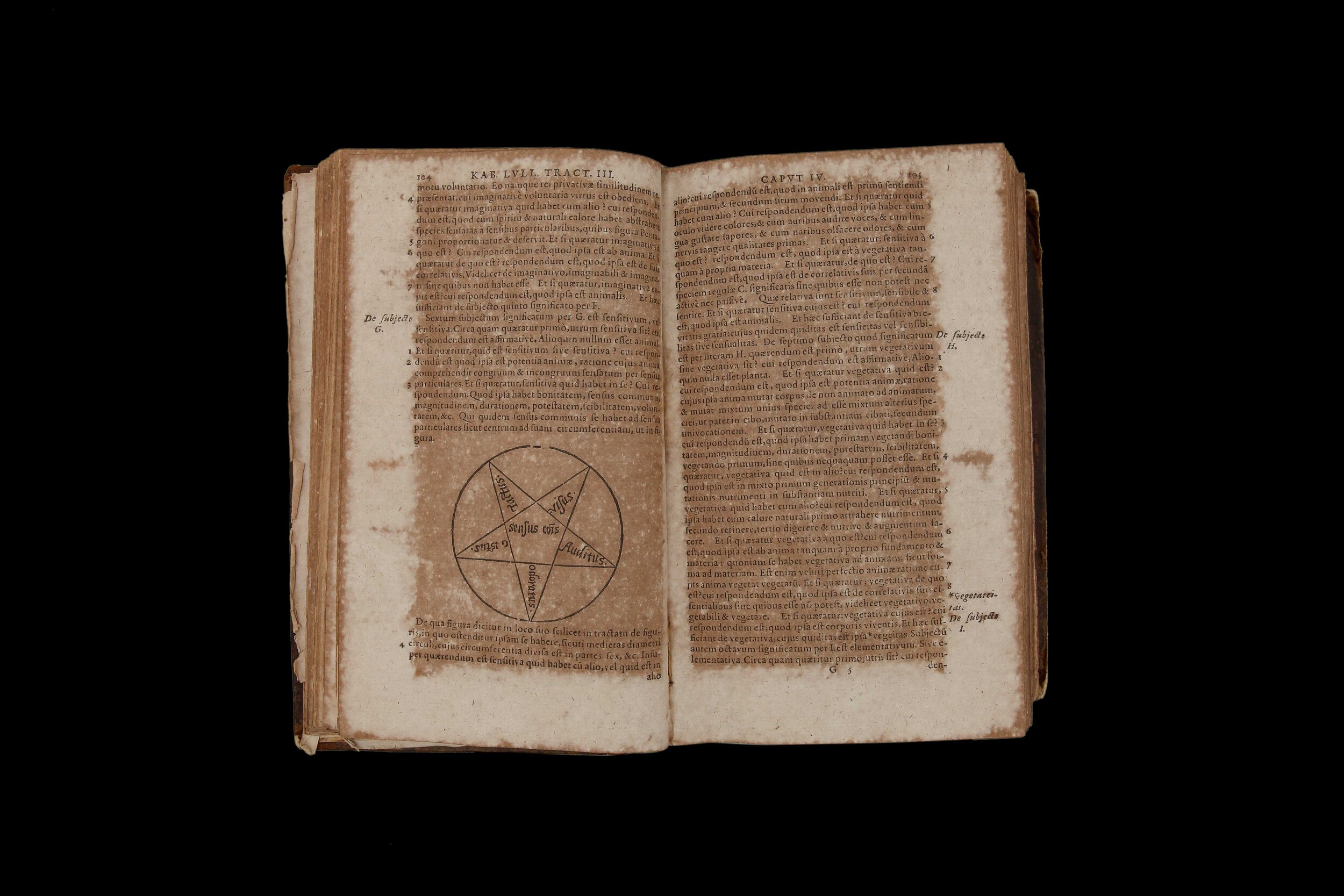

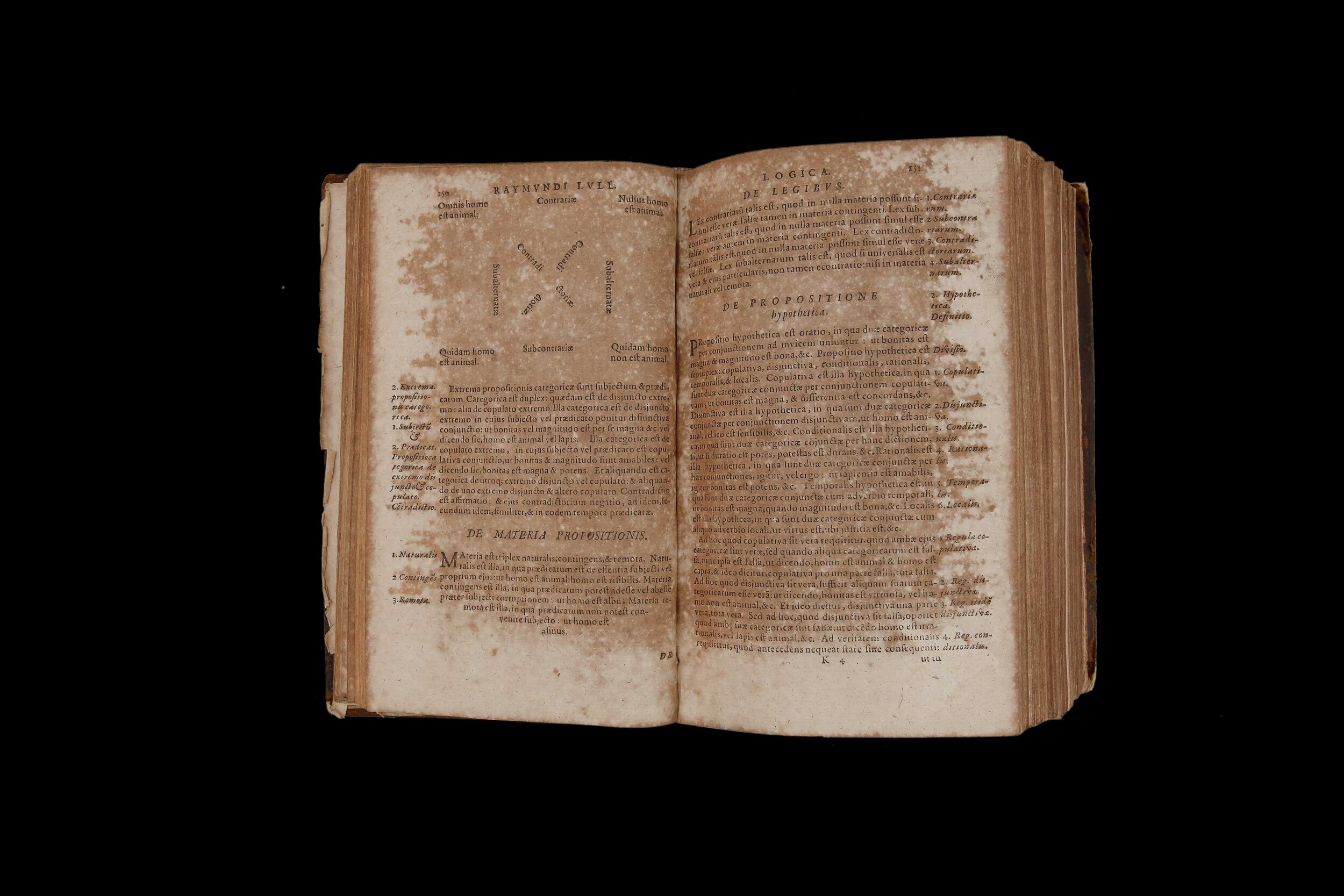

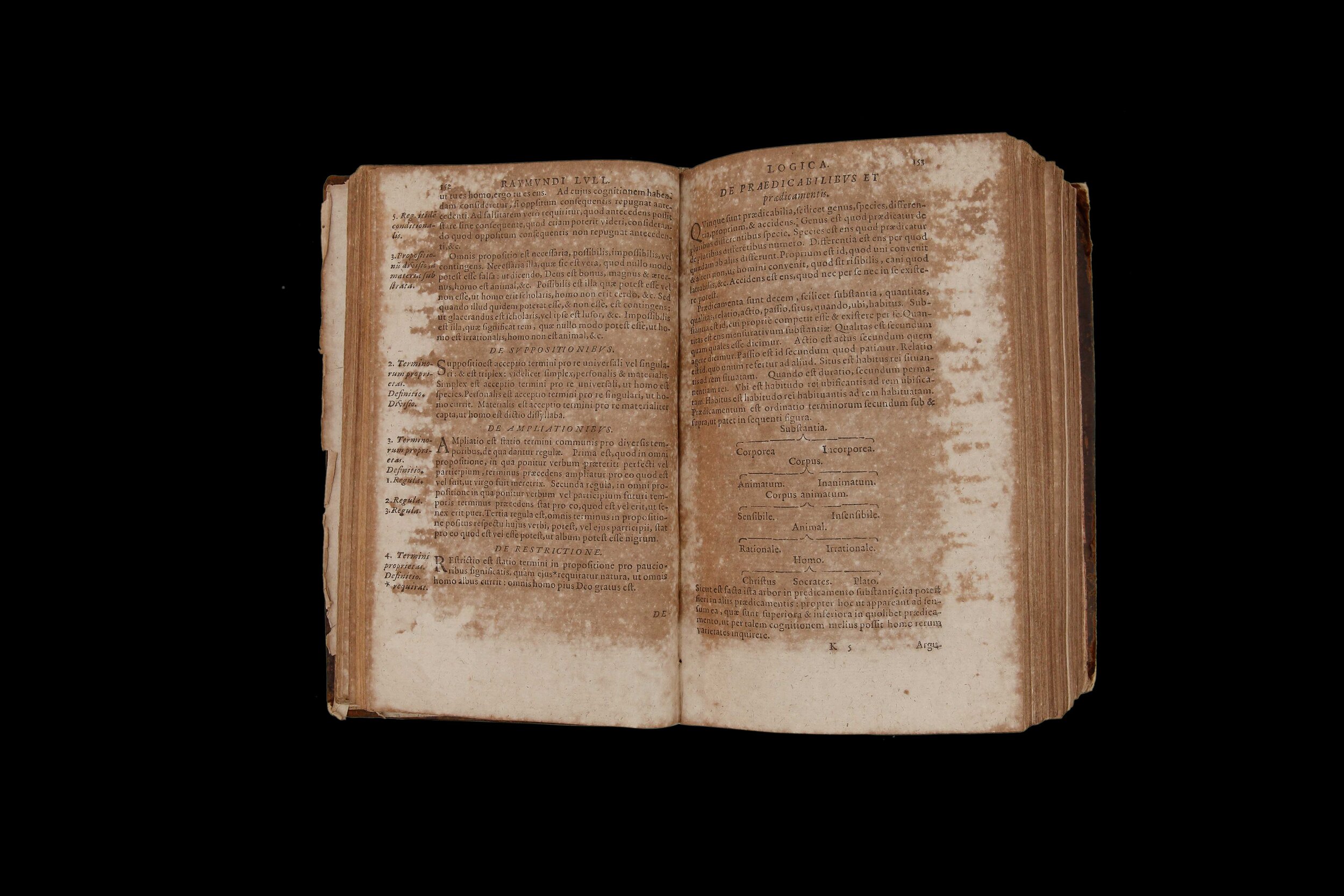

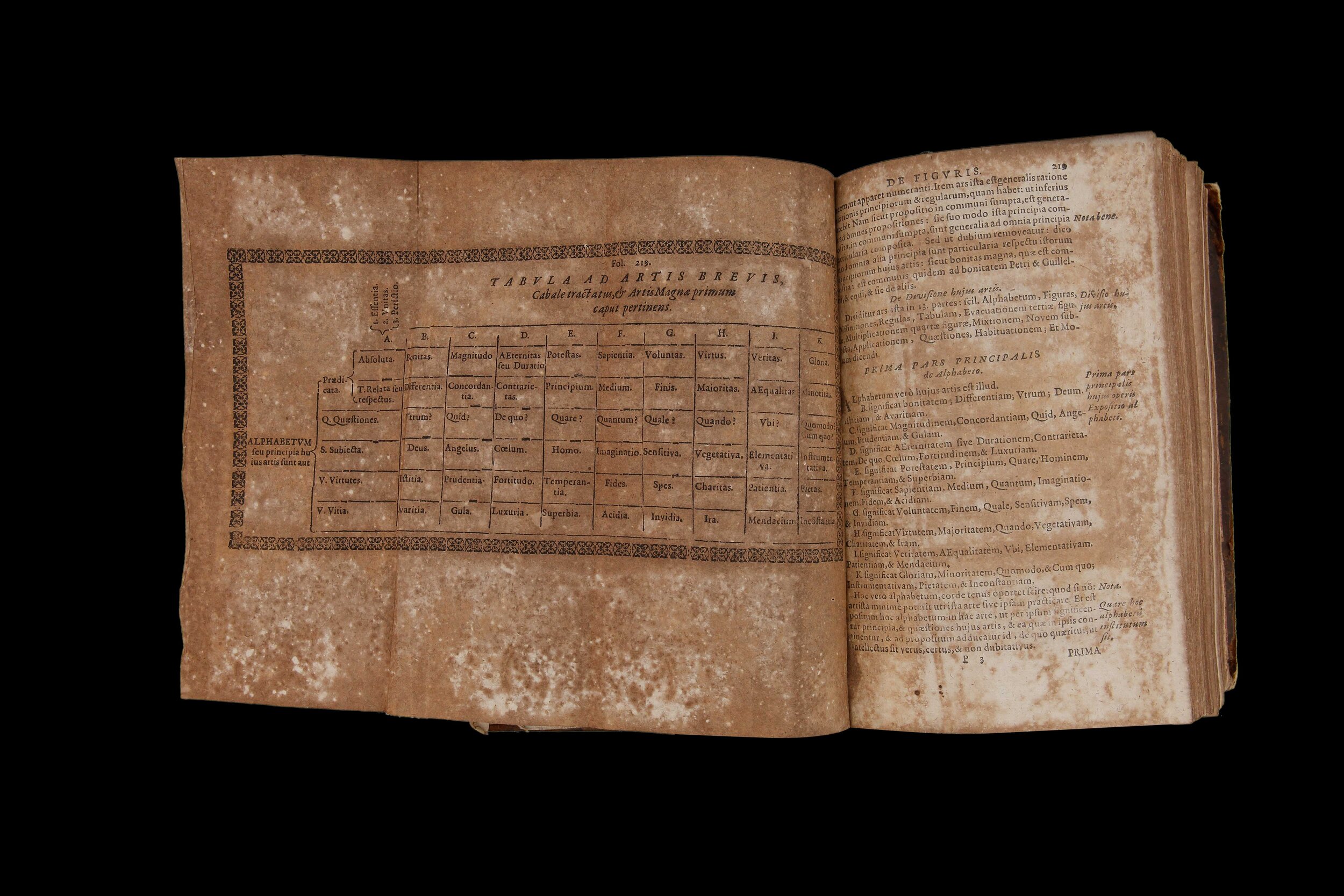

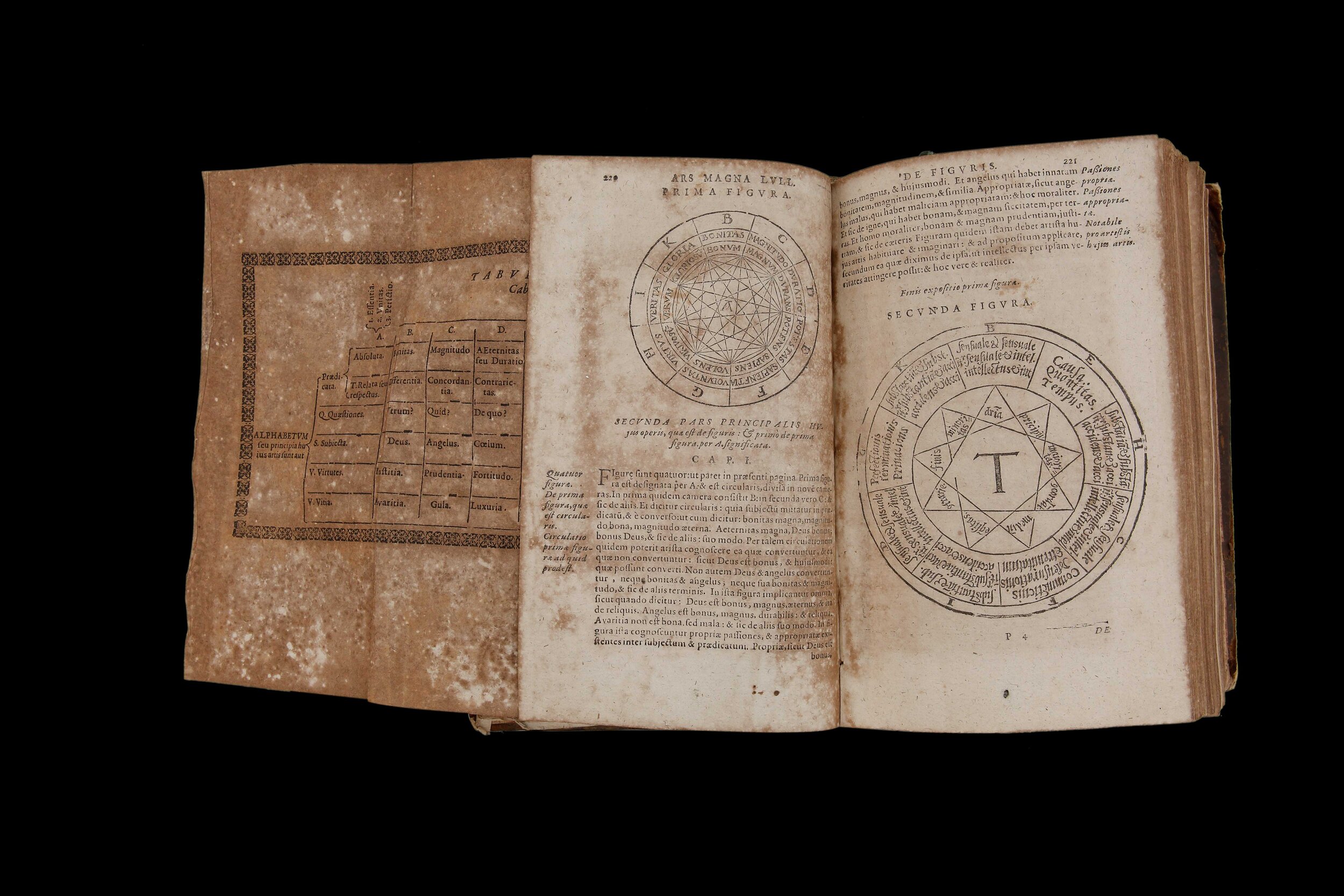

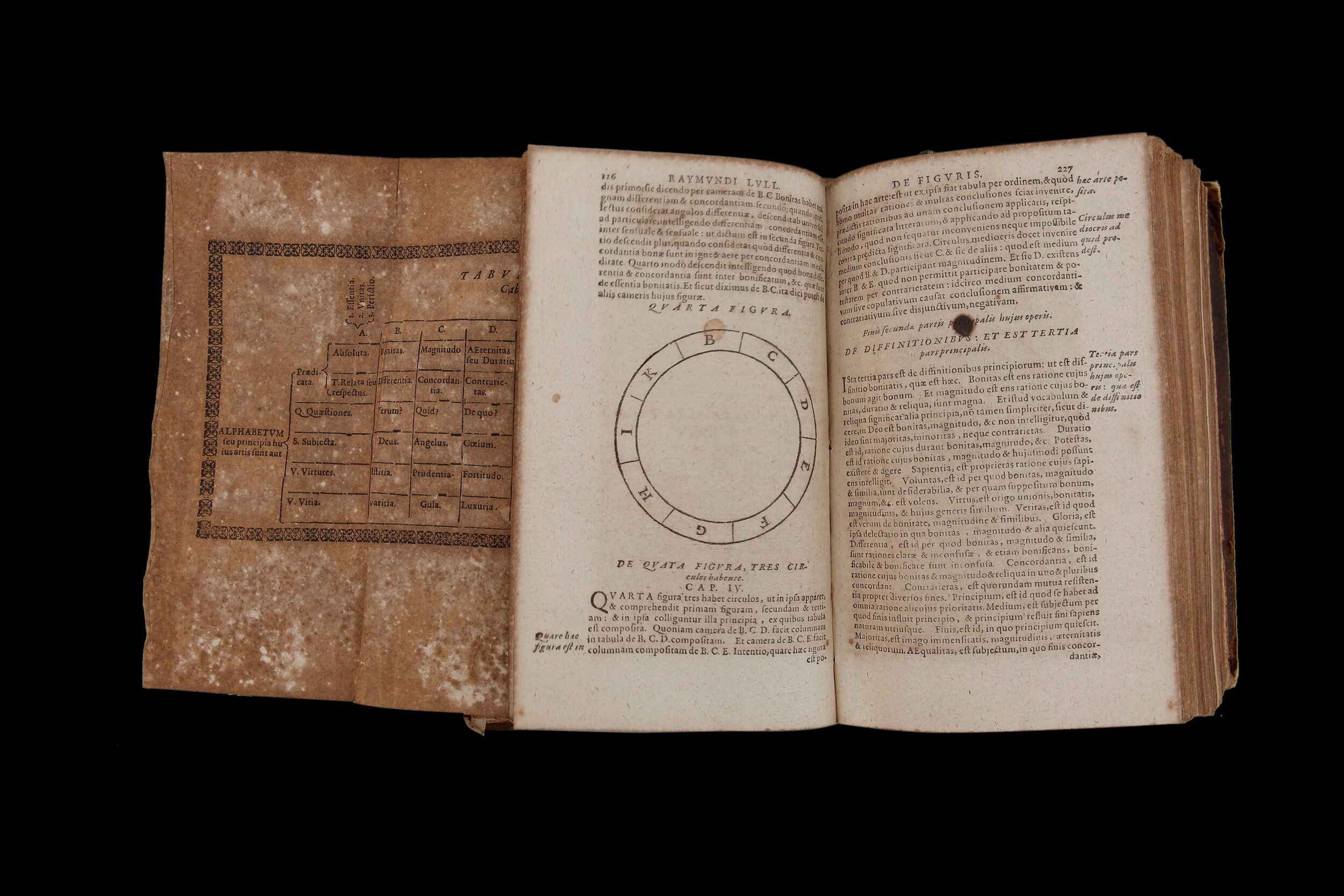

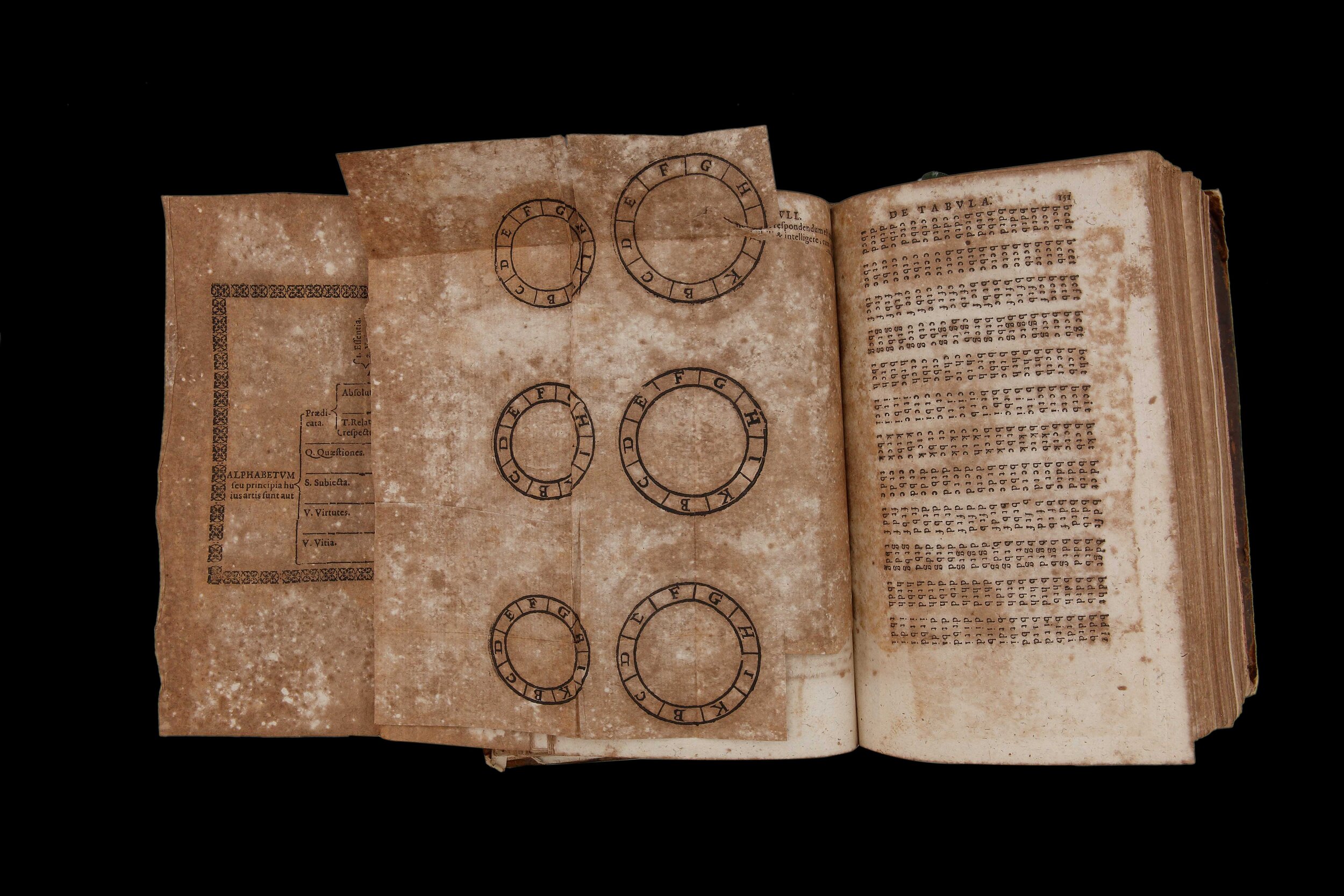

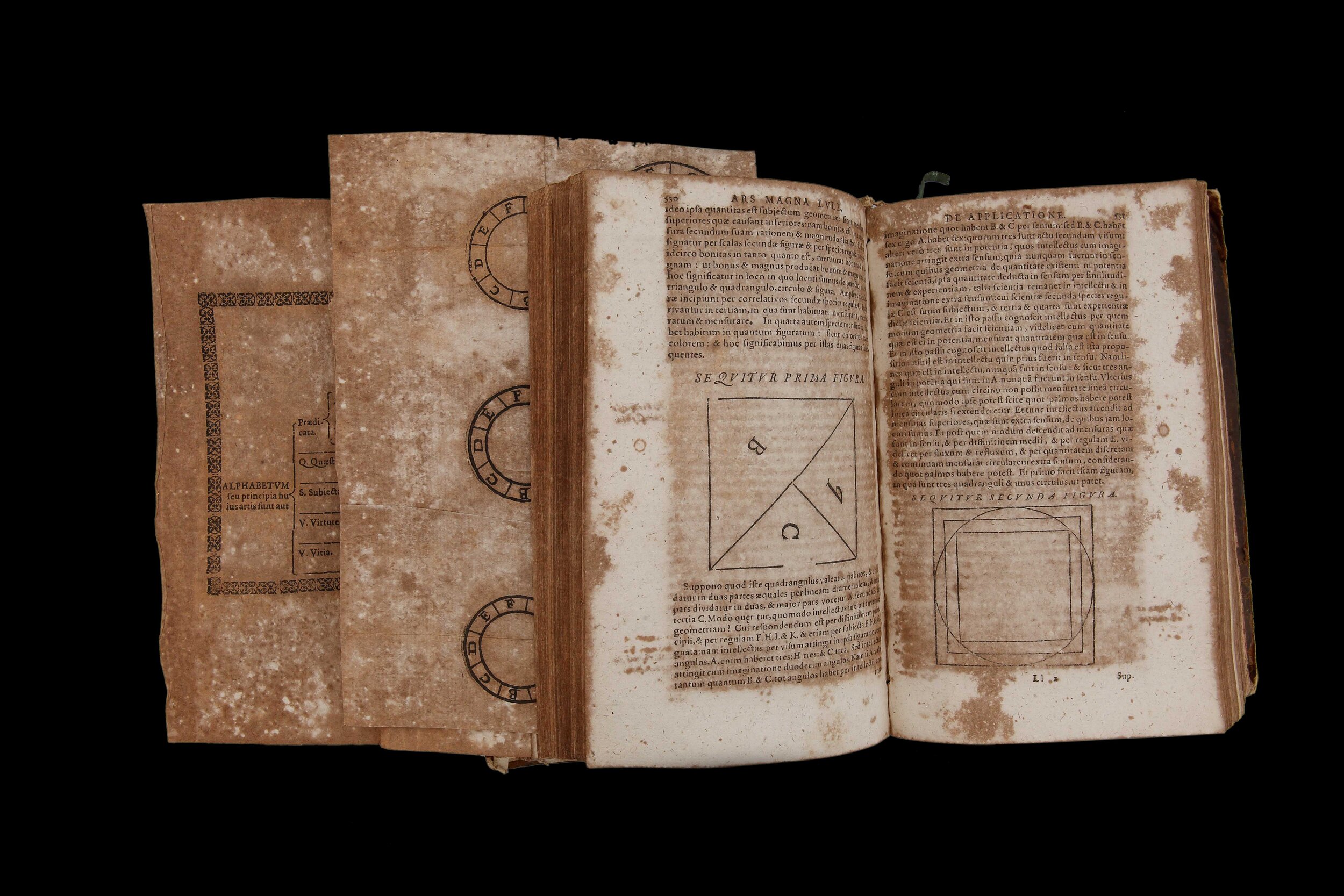

In On the Shadows of Ideas, the intention to approach the light through ideas is described in levels represented by letters from the Latin alphabets (from A to Z) and, in some cases, by Hebrew letters. These letters are engraved on five metal discs that can be rotated to generate different combinations, creating a memory device, a fundamental instrument of the Ars magna, which can be seen as a primitive computer.

Figura 1: Amuleto de invocación del ángel Tarariel

VIII

On the Shadow

(De umbris idearum, fragment, p. 517)

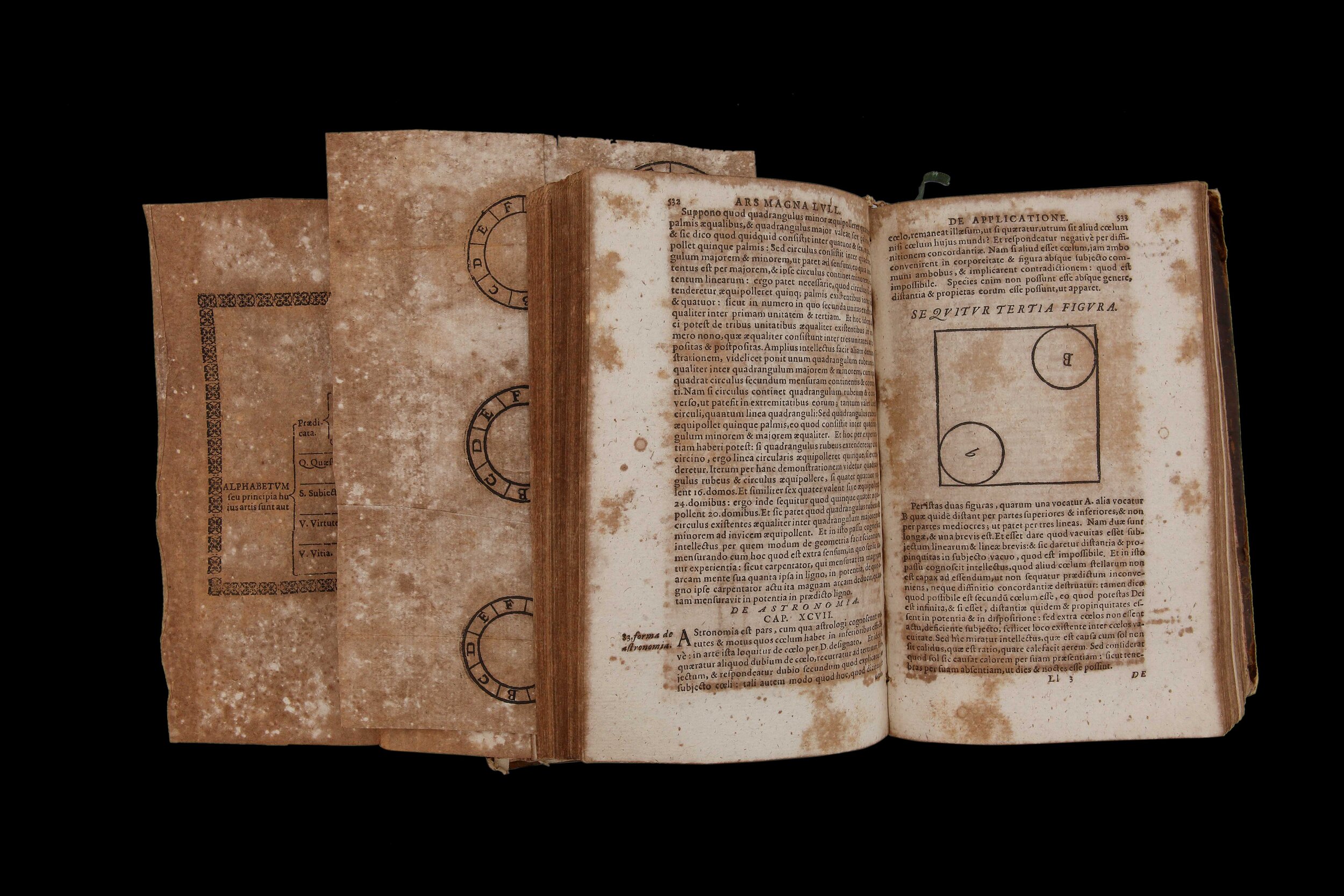

A shadow is a place (loci) deprived of light. This place cannot be endowed with the same accuracy as that mentioned earlier, given the body in the middle that prevents the passage of light. In keeping with the above, clearly, we will perform an experiment with the shadow of trees, or of a tower: reason demands to know the color and the meaning of the shadow; reason sees that the air is diaphanous and that the color that the shadow receives from the sun or from fire is bright in the place where the shadow receives the color of the earth (terræ). For example, a crystal that is subjected to the color red (croceo) is dressed in redness (rubore) and when in a dark environment is dressed in blackness, which is why reason understands light as the color of the sun and of fire. Black is the color of the Earth and diaphaneity is compressed in the air. The whiteness of the water that causes the whiteness of the crystal is due to the fact that the crystal is nothing more than frozen water (aqua congelata). The image of the shadow is the end, where the light of the shadow ends (ad hoc), as evidenced by the second and fourth cases of the Rule of C.[1] Reason asks what causes moon shadows (umbræ lunæ), which generates great doubt, to the extent that it considers the Moon to be a diaphanous body on which the Earth’s shadow appears, but then digresses, because the moon’s shadow does not appear on the Sun, and continues to doubt until it remembers that the Sun is colored by his own light. The light of the Moon comes from the Sun, as heat comes from air, from fire, and this proves Rules G[2] and B[3].